First: A Brief Review

One of my goals for this newsletter is to compile a collection of book reviews of contemporary novels that I loved or otherwise found worth reading, in the hopes that my successes will help someone else find their next good book. So we are going back through the old reading list, and revisiting some favorites. Piranesi sits at the very top of that list.

Piranesi is the story of a man in a House with the sea in it. It is as bizarre as it sounds, and if you haven’t read it, more lovely than you can imagine. The power of the book rests on the personality of its protagonist and narrator, Piranesi, who calls himself a “child of the House;” he is innocent and ignorant, wise in the ways of the Tides that sweep through the vast rooms of his world and yet apparently oblivious to the human capacity for harm. As a narrator, he is unreliable, though not for the usual reasons. I am most familiar with an unreliable narrator who obfuscates, manipulates, or withholds, whereas Piranesi is scrupulously honest, entirely forthcoming. He simply lacks…well, what? The great drama of the reading experience lies in what I felt as a desperate need to know: What Is Going On Here?!

Thus unfolds a truly page-turning mystery. For those who are begging for themes, here’s what I will say: It’s about beauty and truth, power and knowledge, ancient and modern ways of knowing. I was originally put off by the journal-entry style and the archaic language, because I am a little bit of a lazy reader; I don’t want my novels to read like primary sources (alas—not a historian). All reservations vanished by about the third page. I could not put this book down. It is good to the last word.

If you have not yet read Piranesi, stop here! There are (many) spoilers below, and this in particular is a book that you should read unspoiled. Go away!! Come back when you’ve read it! This article isn’t going anywhere.

On Piranesi and C.S. Lewis

Look—you do not need to go and read C.S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew and That Hideous Strength in order to better understand Piranesi; but that is what I did. I got to the end of Piranesi, and the combination of sinister academia and ancient magic recalled to my mind That Hideous Strength.

Both novels—That Hideous Strength and Piranesi—explore the exploitative capacity of human nature and the existence of ancient magic beyond modern comprehension. That Hideous Strength is about a university controlled by a “Progressive Element,” and how this group brings the sinister scientific organization N.I.C.E. down on themselves and the rest of the world. It’s also about how both N.I.C.E. (pursuing an a-moral, non-organic super-human race) and Lewis’s group of heroes (who hold traditional ideas of good and evil and the existence of God), seek the services of a resurrected Merlin. In this story, Merlin embodies an ancient magic from an ancient time now lost to history; both good and evil recognize its power. In this way, both That Hideous Strength and Piranesi treat ancient wisdom as a powerful force, and both novels set up a clear divide between Good and Evil: Good can commune with the transcendent and therefore experience joy, while Evil seeks to wield the transcendent over others and is therefore consumed by it.

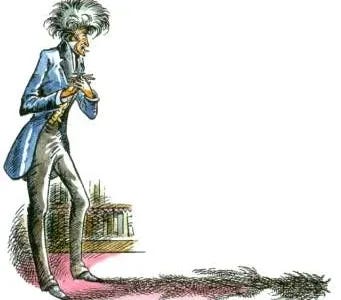

As analysis, this is a little thin, but the parallel is fun. What is demonstrable, though, is that Susanna Clarke grew up reading C.S. Lewis, and that she references his book The Magician’s Nephew throughout Piranesi. This begins with the first epigraph:

“I am the great scholar, the magician, the adept, who is doing the experiment. Of course I need subjects to do it on.”

The Magician’s Nephew, C.S. Lewis

This is a quote from Uncle Andrew, who kidnaps his nephew Digory and the neighbor girl Polly for his experiment. He sends them to a different world, much like Val Ketterley (The Other) sends Matthew Rose Sorenson (Piranesi) to the House. In fact, it is exactly like Val Ketterley: Lewis’s Uncle Andrew is Uncle Andrew Ketterley. And the parallel goes beyond the surname. In The Magician’s Nephew, when Uncle Andrew finds the children in his study, the text reads, “I am delighted to see you,” he said. “Two children are just what I wanted.” In Piranesi, when the Other (Val Ketterley) first traps Piranesi in the House, he says this: “‘Forgive me for not saying anything before now,’ he smiled, ‘but I really am delighted to see you. A young, healthy man is just what I wanted.’” Clarke’s Ketterley is directly modeled after Lewis’s.

Piranesi also references The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Describing his favorite statues in the House, Piranesi writes,

Another—perhaps the Statue that I love above all others—stands at a Door between the Fifth and Fourth North-Western Halls. It is the Statue of a Faun, a creature half-man and half-goat, with a head of exuberant curls. He smiles slightly and presses his forefinger to his lips. I have always felt that he meant to tell me something or perhaps to warn me of something: Quiet! he seems to say. Be careful! But what danger there could possibly be I have never known. I dreamt of him once; he was standing in a snowy forest and speaking to a female child.

This statue is clearly Mr. Tumnus; Piranesi’s dream showed Mr. Tumnus talking to Lucy in Narnia. On a second read-through Piranesi, passages like these strike a particularly aching chord: “what danger there could possibly be I have never known,” writes a man who has been forcibly kidnapped, removed as entirely as possible from his former life, and left in real danger of starvation, drowning, and exposure. But Piranesi sees allies everywhere. He is right about Mr. Tumnus, who in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe warns Lucy of the White Witch’s evil reign. He warns Piranesi, too, implying that the same evil exists in this story.

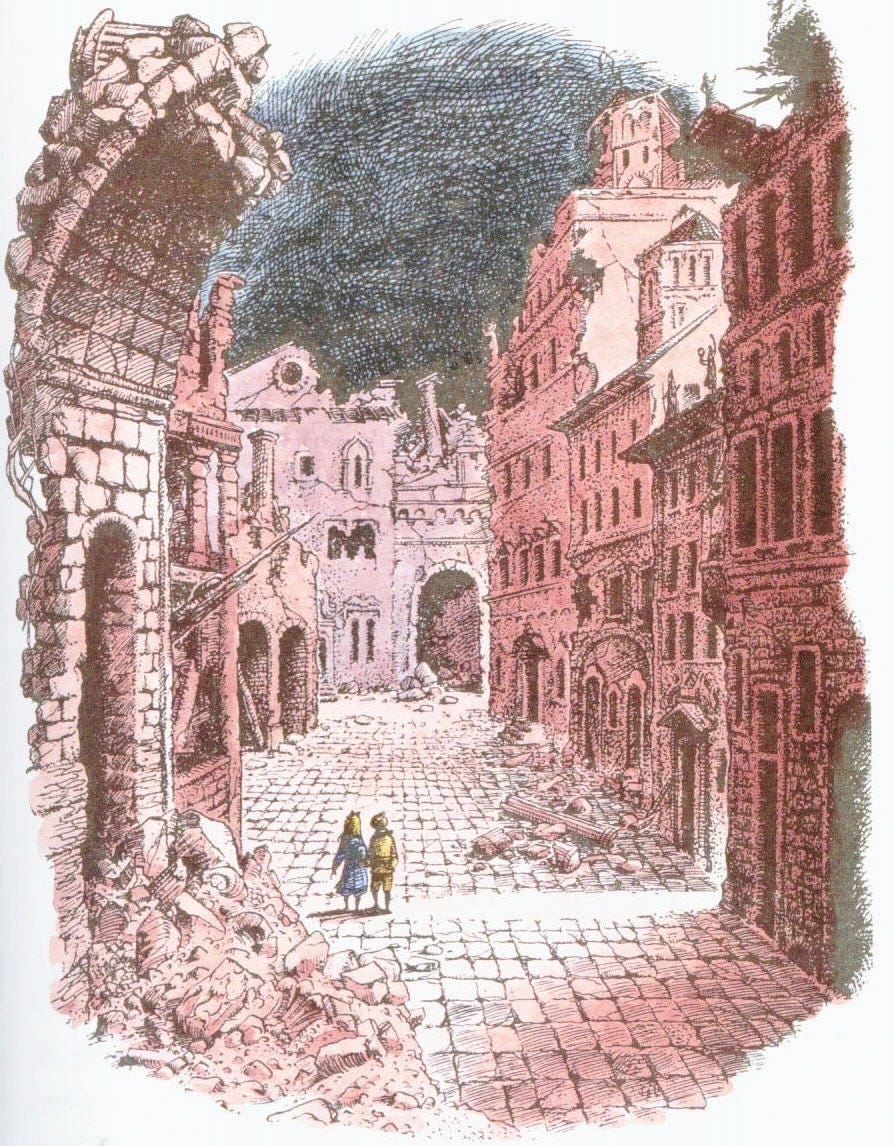

While Piranesi says similar things about the nature of evil, Susanna Clarke’s builds an altogether original world. In The Magician’s Nephew, we learn that Narnia is not the first world that the White Witch has brought to ruin. Charn is a massive, crumbling palace, vast and nearly empty, disintegrating under a dying sun. It implodes altogether when the witch is awakened from her enchanted sleep. In a conversation with The New Yorker, Susanna Clarke said this about Charn:

“I always liked Charn better than Lewis liked Charn,” Clarke told me. In the depths of her illness, she said, “I found having people in the same street with me quite difficult to deal with. Imagining that I was in Charn, that I was alone in a place like that, endless buildings but silent—I found that very calming.”

You can see the seeds of Piranesi’s House here; an endless, ancient House that, rather than being sinister, cares for its lone occupant. In this way Clarke turns Lewis’s world-building on its head; but not its world. In Narnia and in the House, Mr. Tumnus issues his warning. The wicked witch is evil across worlds. Some things remain the same.

So What?

Why trace these affinities? What good does it do anyone to know that Susanna Clarke likes The Magician’s Nephew? What good does it do to compare Piranesi with That Hideous Strength? So what?

First of all, tracing literary allusions is fun. It makes me feel well-read and smart. Everyone likes to feel well-read and smart—at least everyone who’s still reading an obscure Substack newsletter about Piranesi and Lewis.

The practical reason to do it, though, is the hope that recognizing and parsing out the allusion will illuminate something new about the book you’re reading. Sometimes this happens. A knowledge of Virgil improves the reading of Dante. Familiarity with Genesis edifies East of Eden. But to be perfectly frank, I don’t think all my extra reading in this case did much more than reintroduce me to C.S. Lewis.

Piranesi stands so tall on its own. You do not need to know anything about Lewis to appreciate it. But I do think that reading these books together paid off, just not in the way I anticipated. You should read Piranesi to supplement your understanding of Lewis—not the other way around.

In Piranesi, Susanna Clarke offers us another window into C.S. Lewis’s universe (another pool in the Wood Between the Worlds, if you will). And while Lewis may be the better philosopher, Susanna Clarke is the true artist. Piranesi is a literary gemstone, perfectly packaged, achingly beautiful. Lewis didn’t write like this—not really. And how wonderful would it be, to have a world populated with people that think like C.S. Lewis, but are not him? To have more unique individuals adding their unique talents and stories to this conversation about what is good and what is not? More facets to the gemstone. More angles on the truth.

There is one area in which I especially appreciate Clarke’s addition to the conversation, and that is gender. That Hideous Strength is also a book about marriage, particularly one marriage in distress—that between Jane and Mark. And while I agree with Lewis about many things, even within this topic, there is something off about the way he writes Jane’s character. On the one hand, Mark is completely believable. He struggles most with needing to be part of the Inner Circle, which can never be fully achieved—there is always a circle further in. Mark is absolutely believable, absolutely compelling. We all know what it feels like to be Mark, even if that desire to be “in” is not our particular besetting sin.

Jane, however, is far less universally relatable. She sees herself as a rational modern woman who is trying with all her might to reject old-fashioned, cringey notions of religion and womanhood. This is niche; this is a problem only a woman could have. And while it’s not particularly unbelievable, it’s not all that compelling. (At least not to me—please let me know if you feel otherwise). Her great sin, it seems, is an unwillingness to obey Mark, and bear children. This is a simplification, of course. And certainly marriage requires the sacrifice of radical individualism, and I absolutely believe that children are blessings. But Jane’s struggle is only in marriage, while Mark’s struggle is in whether or not he will conquer his desperate need to be part of the in crowd at all costs. He is married too! It seems to me that if Mark is multidimensional and married, Jane should be multidimensional and married. They are both just people, after all.

Even within That Hideous Strength, Lewis himself suggests a limitation. After talking to the Director (the leader of the “good guys”) Jane and Mrs. Dimble, an older married woman, have this conversation: “‘Do you understand his views on marriage?’ ‘My dear, the Director is a very wise man. But he is a man, after all, and an unmarried man at that.’” This description of the Director also describes Lewis at the time of writing. And while Mrs. Dimble does seem to agree with the Director (and Lewis) in practice, I think Lewis was right to undermine his own authority for a moment. It’s as if he wasn’t quite satisfied with the point he was trying to make.

Piranesi, on the other hand, was written by a woman, and a married one. It is dedicated to her husband. The hero of the novel—the person who in the end finds Matthew Rose Sorenson/Piranesi in the House—is a female police officer named Raphael. She is so brave. She is so good. Here is what Piranesi—or whoever he becomes when he leaves the House—says about her:

In Piranesi’s mind Raphael is represented by a statue in the forty-fourth western hall. It shows a queen in a chariot, the protector of her people. She is all goodness, all gentleness, all wisdom, all motherhood. That is Piranesi’s view of Raphael, because Raphael saved him.

But I choose a different statue. In my mind Raphael is better represented by a statue in an antechamber that lies between the forty-fifth and the sixty-second northern halls. This statue shows a figure walking forward, holding a lantern. It is hard to determine with any certainty the gender of the figure; it is androgynous in appearance. From the way she (or he) holds up the lantern and peers at whatever is ahead, one gets the sense of a huge darkness surrounding her; above all I get the sense that she is alone, perhaps by choice or perhaps because no one else was courageous enough to follow her into the darkness.

On the heels of That Hideous Strength, this passage reads like a balm. First, Piranesi describes her with all the words that Lewis would use for the ideal woman: all goodness, all gentleness, all wisdom, all motherhood. A queen in her chariot. And Lewis and Piranesi would both be right. She is all of these things.

But in the second image, she is also brave. This is what it takes to leave the Inner Ring; you have to be willing to walk into the darkness, and you have to be able to go alone. Raphael’s bravery has nothing to do with her sex. Her personhood has nothing to do with her sex.1 That the second image is androgynous opens the door for any one of us to follow Raphael into the darkness.

In Conclusion

Piranesi ends with its titular character back in our world—the one that has lost the magic of the ancients, lost the ability to commune with nature, lost the richness that has fled instead to the House. But here is how Clarke leaves us:

I came out of the park. The city streets rose up around me. There was a hotel with a courtyard with metal tables and chairs for people to sit in more clement weather. Today they were snow-strewn and forlorn. A lattice of wire was strung across the courtyard. Paper lanterns were hanging from the wires, spheres of vivid orange that blew and trembled in the snow and the thin wind; the sea-grey clouds raced across the sky and the orange lanterns shivered against them.

The Beauty of the House is immeasurable; its Kindness infinite.

How hopeful. Perhaps there is, in this world even, beauty and kindness. Perhaps what matters is our perception. Perhaps if we are like Piranesi, like Raphael, like little children, we will not be blind. Perhaps there is something—someone—caring for us mortals, holding us in the midst of these tides. Perhaps the kindness of the house is infinite.

This is certainly the philosophical thread that connects all this material. For Lewis, there are always multiple worlds—multiple planets in The Space Trilogy, multiple worlds to visit in The Magician’s Nephew. In Piranesi, there are at least two worlds, and perhaps more—ours, the House, and untold others. And across each and every one of these worlds—good is good. Evil is evil. And above it all, is something big—something benevolent. Something that might save us. As Piranesi says, “I was in a house with many rooms;…the sea sweeps through the house; and…sometimes it swept over me, but always I was saved.”2

Further Reading

I am not the first to write about C.S. Lewis and Piranesi. See also

’s article “The Actual Point of Literature Most Readers Forget”C.S. Lewis’s address “The Inner Ring,” which discusses the phenomenon he teases out in Mark’s character in That Hideous Strength, is essential reading for any person living in society

For information on Piranesi’s namesake, look into Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi, particularly his collection “Imaginary Prisons”

If you’re smitten with Giovanni Battista Piranesi, this coffee table book looks dope: Piranesi: The Complete Etchings

Article for the MIT Press Reader by Victor Plahte Tschudi about Clarke’s other main inspiration for Piranesi, Jorge Luis Borges, and his inpiration, Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Lisa Allardice’s article for The Guardian on Susanna Clarke and her influences

Fun New Yorker piece on Susanna Clarke by Laura Miller. Exciting quote:

Clarke has begun work on a new novel—one that she doesn’t mind talking about. It will be set partly in Bradford. “It’s an anti-horror novel,” she told me. Which means? “Horror novels have this idea that there’s a kind of secret at the center of the world. And that secret is horrific.” This, Clarke observes, “isn’t much of a secret, really.” Anyone can look around at the world and see that. “So this would be more about the fact that, at the center of things, there’s a secret or mystery, and it is joyful.

A final allusion that didn’t find its way into this piece: “In my Father's house are many rooms. If it were not so, would I have told you that I go to prepare a place for you?” John 14:2

This article contains affiliate links. This means that if you purchase a book linked here, I will receive a small commission, at no extra cost to you. Thanks for supporting The Better Reader!

“There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Galations 3:28

For Lewis, the benevolence is the Christian God. See this quote from The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe: “I am [in your world].’ said Aslan. ‘But there I have another name. You must learn to know me by that name. This was the very reason why you were brought to Narnia, that by knowing me here for a little, you may know me better there.”

This book is a balm to my soul. Her connection to another Inkling, Owen Barfield, is also worth taking a deep dive into.

You called me out. I do like to think that I'm smart and well-read.